Our two scripture readings today both speak about crying. The first reading speaks to the church on earth today, what I was taught as a child to call the church militant, and the second reading speaks to the church in heaven, what I was taught to call the church triumphant. Perhaps those terms are too martial for us today, but by whatever names it is the distinction between the church here and the church hereafter.

Our two scripture readings today both speak about crying. The first reading speaks to the church on earth today, what I was taught as a child to call the church militant, and the second reading speaks to the church in heaven, what I was taught to call the church triumphant. Perhaps those terms are too martial for us today, but by whatever names it is the distinction between the church here and the church hereafter.

In the first reading Paul admonishes the Roman Christians on how to be the church now, and one of the things he tells them they need to do is to “rejoice with those who rejoice and to weep with those who weep.”

The second reading is from the Revelation of St John the Divine. I have a soft spot for the writings of St John the Divine, as I was baptized at the Cathedral of St John the Divine in New York, which is the world’s largest gothic cathedral (so I come by my high church inclinations honestly.)

In this beautiful passage from Revelation, St. John describes the holy city, the New Jerusalem at the end of time and history. He says then there will be no more crying there because God will “wipe away every tear from their eyes.”

So in engaging these two texts about the here and the hereafter, I started thinking about the function of crying in our lives, and especially in the church. I did a little research on crying, and discovered that we don’t know all that much about it. There are several competing theories about why humans cry, including those theories of evolutionary biologists who think it may have some social function.

But there are some things we do know about crying. Research tells us that women cry more easily and more often than men. I found that interesting. Is that the way men and women are wired?

Turns out, no! Research shows that the differences only show up after early childhood, so that the difference seems to be a social construct. And that sounds right to me, because when I was growing up crying was especially discouraged for boys. My father, who was otherwise a very kindly man, would say to me when I cried, “Men and boys don’t cry.” In those days if you cried you risked being called a “crybaby.” So throughout most of my life I avoided crying as much as I could, at least in front of other people.

So it is ironic (as life is so often ironic) that one of the stranger symptoms resulting from the traumatic brain injury I got 15 years ago is my tendency to cry at odd times. I cry while watching sappy jewelry commercials on TV (“Every kiss begins with Kay”) or videos on Facebook of a room full of puppies. And there is nothing I can do about it, which is humbling to say the least.

This hair-trigger crying is the result of something called “emotional lability.” I call these unwanted tears my “silly weeping.”

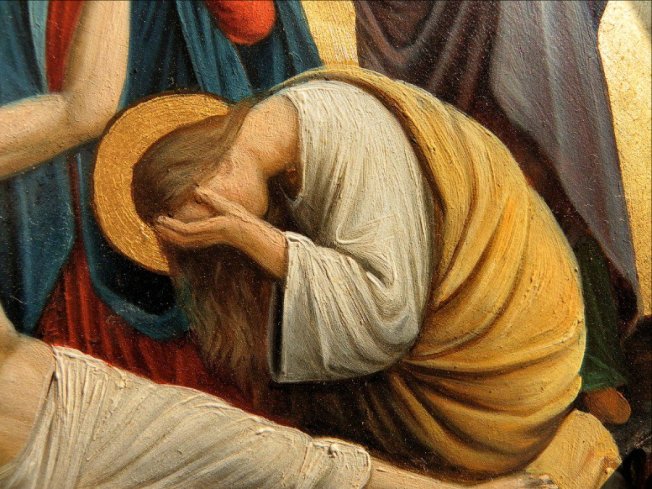

But there is another kind of weeping I have come to recognize as “holy weeping.” This is weeping for things that really matter: weeping in human solidarity with those who suffer; weeping in genuine grief, loss, or remorse; sometimes weeping in unalloyed joy.

I confess that I often weep quietly in church when I am deeply moved by a scripture, a piece of a hymn, or the truth of God’s love told well in a sermon. I can’t stop weeping when I hear Dr. King’s “I have a Dream” speech.

Not that the church has a monopoly on such holy weeping. How many of us have had a deeply emotional response to the good, the true, or the beautiful wherever we encounter it? People get choked up at Tanglewood on hearing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, as well they should.

That being said, there is a particular important function in weeping together that is part of what defines a Christian congregation.

Because Paul’s admonishment to Christians to “rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep” is an important part of what makes a congregation.

A congregation is a communal context for us to do our holy weeping together. That is part of who we are: We “weep with those who weep,” and I am convinced that in these holy moments somehow God weeps with us.

Such holy weeping together takes tangible form here among us during our Joys and Concerns time in worship. When we share our joys and concerns we take Paul’s admonition seriously to share with others the deepest matters of our hearts.

This solidarity one with another reminds us of our inter-connectedness in the Body of Christ, to use Paul’s prevailing metaphor for the church, and also reminds us of our larger inter-connectedness within the whole human family of which we are a part.

There is so much to weep about in our broken world. On any given Sunday heart-breaking concerns are raised here in worship. Many are quite close to home and personal: the death of a loved one; the struggle of someone with an injury, illness or addiction.

Some of our concerns are far from Stockbridge, but no less cause for weeping. So we weep for the epidemic of suicides among our young and our veterans. We weep for the vast racial divide that still afflicts our nation’s soul.

One of the stories in the human family that has been breaking my heart in these past days is the migrant crisis in Europe. This month alone over 100 migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea when the ships carrying them and their dreams of safety have sunk.

I heard a news story this week from the BBC on Public Radio that especially touched my heart. Perhaps you heard it, too. It was about an Italian carpenter who makes crosses from the wood of the wreckage of these boats on his island and gives them to the survivors.

His name is Francesco Tuccio, and he lives on the small Mediterranean Island of Lampedusa. On the 3rd of October, 2013, a flimsy boat carrying refugees from Eritrea and Somalia sank off the coast of his island. There were 500 people on board when the overcrowded boat caught far, capsized and sank. Only 151 survived.

Some of the survivors were Eritrean Christians, fleeing religious persecution in their home country. Mr Tuccio met some of the survivors in his church and, frustrated by his inability to make any difference to their plight, he went and collected some of the timber from the wreckage of their boat and made each of them a cross to as a symbol of hope for the future.

The Director of the British Museum heard the story about the crosses and contacted Mr Tuccio to see if it could acquire one for the Museum’s collection. Mr Tuccio made and donated a cross to the collection as a symbol of the suffering and hope of our times. When the museum thanked him he wrote “it is I who should thank you for drawing attention to the burden symbolized by this small piece of wood.”

The cross went on display in the British Museum in October. The BBC report I heard interviewed several people who were viewing the cross at the museum and many of them were weeping and visibly moved.

And I wondered, “Why the cross?” The cross has been a preoccupation of mine for most of my adult life, but why, I wondered, does this symbol speak beyond those who self-identify as Christians.

Part of it is surely what Francesco Tuccio himself said, that the cross is a symbol of hope.

But how did the cross become a symbol of hope, because it certainly didn’t start out that way?

My New Testament professor William Robinson, used to say how peculiar it is that in our culture people wear crosse around their necks as jewelry. It would be as if we would wear little jewelry electric chairs around our necks.

Because that is what the cross was: a means of execution. The cross was a symbol of Roman state violence, a horrific instrument of pain and suffering used to intimidate and control the populace.

Surely something to weep about, and there was great weeping when Jesus met his cross. In Luke’s account of Jesus’ death a large crowd of weeping women followed him as he carried his cross through the streets.

So, the cross didn’t start out as a symbol of hope, but as the very place where we humans crucified the Lord of glory. When I think about it I recall the words of the old spiritual Were you there when they crucified my Lord: “Sometimes it causes me to tremble.”

It is only in the light of Easter, when God raises Jesus and is victorious over the powers of sin and death that the cross becomes a symbol of hope, a symbol of divine love that overcomes even the very worst that can happen in life.

This divine love is holy love. It is not an easy love, but a hard love for a hard world. The love that the cross symbolizes is not warm and fuzzy; it is not sentimental. It is not a room full of puppies.

No, this is love found and known in the midst of, and on the other side of pain and suffering, and I tell you in truth I speak from experience.

This is love found and known on the other side of the great weeping that we must do for ourselves, and for our world.

So a Christian faith that takes the cross seriously invites us to ask ourselves: What parts of our lives need weeping over?

We need to ask ourselves: Where do we hurt? Where do we know pain and suffering?

And anyone who can say, “I have no pain” needs to ask, then who in your life do you know that does have pain, and what can you do to help?

And also ask: who have you caused pain to? By decisions you’ve made or not made.

We need to ask ourselves such hard questions to know the truth of our own vulnerability. For it is in that vulnerability that we best know our God, the crucified God, the God we meet in Jesus.

So yes, we weep with those who weep to comfort and console them, but this holy weeping is not only for them but also for ourselves. Because, when our hearts are moved (and sometimes even broken) we get in touch with our deepest humanity.

And, at our best, this heartbrokenness can inspire us to action, for if something is worth weeping for it is worth acting on. I’m thinking of that heartbreaking photo last year of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, washed up dead on a Turkish beach. His family was desperately trying to emigrate to Canada, but were refused by the Canadian government. The power of that photo moved hearts and led to Canada changing their immigration policy.

When we weep we connect with the power of human compassion. I am praying that the church can find its true voice amid its tears and speak truthfully and firmly against the fear-mongers and xenophobes who seem to so dominate our political discourse around immigration.

It is a scandal to me that so many of our Christian brothers and sisters have lost the capacity for compassion. The root of the word compassion is “shared suffering.” One definition of compassion is: “sympathetic pity and concern for the sufferings or misfortunes of others.”

Some have said to me, “Well, what about taking care of our own. Our homeless, our hungry, our veterans!” And it is true, we need to do better for so many. But love is not a zero-sum game! Compassion can’t be doled out in teaspoons. God’s extravagant love is our model. because God loves us from abundance and not from scarcity.

No we can’t do it all, it’s true, but everything we can do matters and so we must do what we can.

Our holy weeping means we are in touch with our compassion. And that’s who we are as Christians. We have a suffering Lord and a cross at the center of our worship. We weep with those who weep because unless we do it makes us something less than fully human. Our human compassion is a mirror of God’s compassion, and it is one of the things we mean when we say we are made in the image of God.

And this God, our God, promises to be with us (and not against us) whatever life throws at us, whatever pain and suffering comes our way.

And finally, on the other side of time and history, with the church triumphant, this God promises to be in our midst, God with us.

And there, this God promises, there will be no more Death.

There will be no more mourning. There will be no more crying.

There will be no pain or suffering anymore, for the former things will have passed away.

So I imagine that in the worship service of the heavenly court there will be no more concerns, only joys!

There will be no more weeping, only praise,

And great rejoicing! Amen.

(I preached this sermon at the First Congregational Church (United Church of Christ) in Stockbridge, Massachusetts on January 24, 2016)

OH, FOR CRYING OUR LOUD!!! Thanks for the inspiration. God bless!

Richard, your amazing talk to retired pastors has wide applicability to all retirees. How well done!

Happy Birthday,

Will Newman

UCC LC Member