(This article first appeared on the Faith and Leadership blog of Duke Divinity School on on March 17, 2010.)

If the main reason you become a pastor is to promote some cause, then your soul is in danger, and so is the congregation’s.

(This article first appeared on the Faith and Leadership blog of Duke Divinity School on on March 17, 2010.)

If the main reason you become a pastor is to promote some cause, then your soul is in danger, and so is the congregation’s.

Book Review: “Useful Wisdom: Letters to Young (and Not-so-Young) Ministers” by Anthony B. Robinson, Cascade Books, 2020. (Link to the book at Wipf and Stock here.)

By Richard L. Floyd

This little book is well-titled, for it is both useful and wise. In the interest of transparency, let me say that I have known Tony Robinson as a friend and interlocutor for decades. During that time, I have admired his many writings, which are clearly and concisely written, and grow out of his pastoral experience and long years as a church consultant. Continue reading

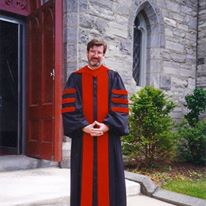

On this day forty-five years ago, September 21, 1975, I was ordained into the Christian Ministry of Word and Sacrament at the Newton Highlands Congregational Church, United Church of Christ, in Newton Highlands, Massachusetts. I was 26. Continue reading

On this day forty-five years ago, September 21, 1975, I was ordained into the Christian Ministry of Word and Sacrament at the Newton Highlands Congregational Church, United Church of Christ, in Newton Highlands, Massachusetts. I was 26. Continue reading

Greetings from the Berkshire Hills. I’m Rick Floyd and I’m Pastor Emeritus of the First Church of Christ in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

Greetings from the Berkshire Hills. I’m Rick Floyd and I’m Pastor Emeritus of the First Church of Christ in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

It will be 50 years ago next year that I walked down the Andover Newton hill and took the MBTA from Newton Centre to Newton Highlands for a job interview to run a coffee house at the Newton Highlands Congregational Church. Continue reading

My friend Horace Allen died on February 5. Horace was an important ecumenical Christian scholar of worship and liturgy.

My friend Horace Allen died on February 5. Horace was an important ecumenical Christian scholar of worship and liturgy.

The Reverend Doctor Horace Thaddeus Allen. Jr. received his B.A. from Princeton University, his M.Div. from Harvard Divinity School, and his Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary. Continue reading

Once again as the old year passes and the new year beckons, it is my custom to look back at my most popular posts of the year. Some years a theme emerges, and this year it is the passing of old friends and mentors. Three of my professors from seminary died within a few weeks of each other early in the year, and my tributes to and remembrances of them were among the most popular posts.

Once again as the old year passes and the new year beckons, it is my custom to look back at my most popular posts of the year. Some years a theme emerges, and this year it is the passing of old friends and mentors. Three of my professors from seminary died within a few weeks of each other early in the year, and my tributes to and remembrances of them were among the most popular posts.

Here in order are the most visited new posts from 2016:

A Prayer for Christmas (and for our time) from Karl Barth

A Tribute to Meredith Brook “Jerry” Handspicker 1932-2016

“Of Fig Trees and Second Chances” A Sermon on Luke 13:6-9

Remembering William L. Holladay

Let us not treat this wound too lightly. Reconciliation requires repentance

Mike Maguire and Me: Recollections from Long Ago

“Rich in Things and Poor in Soul” A Sermon on Luke 12:13-21

A tribute to Max L. Stackhouse

“Holy Weeping’ A Sermon on Romans 12:19 and Revelation 21:1-4

“Known knowns, known unknowns,” and the New Testament

As in previous years certain posts have had real staying power. Many of these are sermons that desperate preachers found on search engines. For example, my sermon for the Third Sunday of Advent was the number one entry if you Googled “Sermon for the Third Sunday of Advent.” Consequently, I saw extraordinary spikes in traffic the week before.

So here are my all-time top ten posts since I started “When I Survey . . .” in 2009:

Why did Jesus refer to Herod as “That fox” in Luke 13:32”?

“Rejoice! Rejoice!” A Sermon for the Third Sunday of Advent

God Gives the Growth,” A Retirement Sermon

“The Lord Will Provide:” A Sermon on Genesis 22

“There is nothing to be afraid of!” A Sermon on Psalm 27:1-2

An Ordination Sermon: The Secret Sauce of Ministry. A Recipe in Two Parts

“God With Us” A Sermon for the Fourth Sunday of Advent

“Behind Locked Doors” A Sermon on John 20:24

“The Message of the Cross” A Sermon on 1 Corinthians 1:23-25

Another milestone for this blog is that it reached 100 followers this year. So I thank you all for your interest and support. Come back and visit now and again in 2017.

“For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven,

and do not return there until they have watered the earth,

making it bring forth and sprout,

giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater,

so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth;

it shall not return to me empty,

but it shall accomplish that which I purpose,

and succeed in the thing for which I sent it.” (Isaiah 55:10-11)

The title for today’s gathering was announced as “Getting from There to Here.” As I reflected on it I wondered if perhaps “getting from here to there” might be more apt. “Here” being the text in front of you, to “there, ” the sermon. That works.

But as I thought more about it I saw the wisdom of “from there to here.” From “there,” “the strange new world of the Bible,” to “here,” the world we live in. And I thought of some of the various locutions we have used over the years to capture this movement from text to sermon, such as “from text to context” or “from Word to world.”

Then I considered the many ways I have approached the writing and preaching of sermons, and I realized this movement from text to sermon was more dialectical and less linear than any of these ways of speaking about it.

As I thought about it, the more I liked the sub-title of The Hobbit, which as you may know is “There and back again.” So perhaps “here to there and back again” is more like it.

From here to there and back again describes a journey that is not just a straight line, but rather more like a journey without a map or even a predetermined end. And I like this way of thinking, because it captures how I have experienced sermon preparation in my four decades as a preacher.

I start with a Biblical text, and then I live with that text throughout the week on my journey, revisiting it and wrestling with it and worrying it until I begin to hear something of the voice of God in it, and by then the contours of the journey begin to show themselves, as do even the purpose of the journey and it’s destination.

The process seems to take on a life of its own, which is another way of saying that the Word of God is alive. I like today’s Isaiah text where God uses the agricultural metaphor of rain and snow watering the earth and making it produce to describe the way his Word works, “It shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and succeed in the thing for which I sent it.”

And I want to say a bit about what I mean when I say “the Word of God,” which can mean one thing or another, even sometimes one thing and another, or even three things depending on the context.

One way of thinking about this that has helped me comes from Karl Barth. He wrote about the threefold understanding of the Word of God. First, there are the written words of the Bible, then there are the spoken words of the preacher, and finally, and most importantly, there is the living Word, Jesus Christ.

This living Word is mediated through both the written words and the spoken words. The prayer I began my sermon with today is based on this idea: “Through the written word, and the spoken word, may we behold the living Word, even Jesus Christ our Lord.”

And that is not to say every text needs to be understood Christologically (although it can be), as in the text we have from Isaiah today. But to say there is a living Word is to say that whenever we hear the Word of God as direct address to us, it is the same Word of the same God, who came to us and for us and became the Word made flesh.

So when I talk about the Word of God in sermon preparation, it may be a reference to the text itself, the words, or to the proclamation in the form of a sermon, the Word preached, or to both, but the goal of the journey is, through the finite human words of the text, and the finite human words of the preacher, to transcend this finitude to hear the living Word of God. And I believe this is the primary task and challenge of preachers, and of the church, for that matter.

Let me say a little bit more about the words of the text and the words of the preacher as the Word of God. I think of them by analogy to the doctrine of the two natures of Christ. Jesus is truly human and truly divine, not half and half or some other percentage.

And in much the same way (although not identically) the words of our Scriptures, the Old Testament and the New Testament, are truly human and truly divine. Human in every way, written (and edited) by human beings, and truly divine through the agency of the Holy Spirit of God who inspired the writers to write them, the same Holy Spirit the church invokes when we read them.

And the same thing can be said about the words of the preacher. A sermon is not written in some special spiritual words, but in the same human words that we use in everyday speech. Since everyone in this room is a preacher I don’t have to belabor the point that we are all human, even all-too human. Yet the Holy Spirit that inspired the writers of Scripture is the same Holy Spirit that inspires the preacher, and the same Holy Spirit that the church invokes and invites as it prepares to hear the Living Word of God from the frail words of scripture and the frail words of the preacher.

This is admittedly a high view of preaching, and some might say it claims too much for the preacher. I would say quite the opposite. It is the views of preaching that put emphasis on the personality and performance of the preacher that claim too much for the preacher.

The claim that the preacher is to be a minister of the Word of God is much like the church’s understanding of the celebrant at the eucharist. The principal was established early in the church during the Donatist controversy. The Donatists were heretics, so the question arose whether the baptisms they performed were valid. And the church agreed that “the efficacy of the sacrament does not depend on the sanctity of the celebrant.” So the preacher may be more or less gifted with the homiletical arts, but it is not those gifts that are decisive. What is decisive for the preacher is that he or she has been set apart to deliver the church’s proclamation, so that the church may hear in it the living Word of God. It is not about the preacher. It is about the church hearing the Word of God.

This is a (nearly) sacramental view of preaching, that the preacher should say what the sacrament shows. And in both cases neither the preacher nor the celebrant has control over the Holy Spirit of God, as if we somehow could control God. No, Christ is not truly present in the sacrament nor truly alive in the preached Word because we invoke his name, but rather because he himself commanded us to do these things and promised to be present with us when we did.

So with this high view before us, and a text in front of us, how do we get from there to here or from here to there and back again?

The first thing I want to say about approaching a text is the expectation that God will speak through it. Which is to say that the high view I propose operates out of trust. I think it was Richard Hayes who wrote about a “hermeneutic of trust.” For decades we have been talking and hearing about “a hermeneutic of suspicion,” and that has had its place as an corrective to the Scriptures being misused as instruments of oppression and injustice, “texts of terror,” as my teacher Phyllis Trible so eloquently called them. But there has been a heavy price to pay for the widespread “hermeneutic of suspicion” that has so pervaded the academy for decades, in that many preachers now reflexively distrust the texts.

And I think it is sometimes necessary and appropriate to distrust a text, but it shouldn’t be where we start. Sometimes distrusting a text along the way will lead you to the Word of God.

So the text is in front of us. Perhaps it is an assigned text from the lectionary. I like that, because I can be a lazy sinner who is inclined to make my favorite texts do tricks for me, but that is just me.

Perhaps the Bible is open on our desk, perhaps it is on our computer screen or smartphone, but there it is. First things first: read the text.

Read it in expectation that God’s Word can be heard in it, but don’t rush to decide what it means or even what it has to say. Texts need time. They need to be listened to. I have always described my sermon preparation as inhabiting a text. Living in it.

Another good way to think about it is to “stand under” the text so as to understand it. And the preacher stands under the text along with the rest of the church.

I am really talking about hermeneutics now more than the homiletical side of things. So you all know the various ways to worry a text into view. Read it in the original languages if you have them. Read it in several translations. Look up any key words or phrases in a Bible Dictionary. Take a stroll through some commentaries. Find out its genre and its original context. In other words do your homework. I once preached a sermon that involved Herod, and added “you remember him from the Christmas story.” My dear friend Luther Pierce, a retired UCC minister, shook my hand at the door and said, “Good sermon, Rick, but you conflated Herod the Great with Herod Antipas. Different Herod.” Oops!

So once you’ve done your due diligence and you have the text in your grasp, reflect on the context. Those of you who were preaching in the weeks after 9/11 may recall that the Common Lectionary texts were from Jeremiah and Lamentations, texts we had all avoided in the past because they are horrible cries of despair for the destruction of Jerusalem. All of a sudden after 9/11 texts about the city of devastation and the burning tower became eerily contemporary.

Which is to say contexts change. The immediate context of any preacher is the life of the congregation, and when I talk of inhabiting a text, I am referring to going about one’s pastoral duties with the text in mind. From here to there and back again.

Then there are the larger contexts of the communities in which we live and the country and world we are a part of. Sometimes contexts demand our attention.

We rarely get the kind of compelling clarity about the relationship between text and context that we got after 9/11, but keeping the text in mind as we think about the multiple contexts will often show us the way to go, the particular context that needs to be addressed by the Word of God.

The dialectic of the journey of text to context and context to text means straddling two worlds with the hope we can find in them the same story.

I had the privilege of preaching my daughter’s ordination sermon back in June, and afterwards Mary Luti said, “I like the way you went back and forth from the story in the scriptures to your story now.” And her comment made me realize that I preach that way because to me it is the same story.

I immediately thought of Hans Frei’s The Eclipse of Biblical Narrative, a wonderful and important book. Frei’s thesis is that prior to the Enlightenment Christians inhabited the Biblical Story. They understood it as their story. They were part of it. The Enlightenment changed that as we held the story at arm’s length like any other observable phenomenon.

The task of the preacher is to repair the breach; to make the Christian Story our story again. I am reminded of Bruno Bettelheim’s book, The Uses of Enchantment, where he argues for the re-enchantment of the world for children through fairy tales.

Letting the words of scripture and the words of the preacher be the Word of God for God’s people requires a similar kind of re-enchantment. It means the church realizing that the Story isn’t just back there, but is still going on and we are characters in it.

Let’s look quickly at our Isaiah text for today to see how this might be done. The text is from Isaiah of the Exile and the context is a people who have no reason to be hopeful, since they have lost the three pillars of their identity, their temple, their land and their nation.

The promises made to their ancestors Abraham, Isaac and Jacob seem null and void. Their prospects seem dim, their possibilities few.

Into this context God speaks through the prophet. “My ways are not your ways, my thoughts are not your thoughts.” “You know that rain and snow we sometimes get in the desert? That is what my word is like. It will not come up empty. It will make happen that which I promised.”

And that is what the Word of God sounds like.

And when we hear this story, can it speak to us, where our prospects seem dim and our possibilities few? Can it speak to a declining church too often eager to call it a day? Can it speak to a nation full of grave injustices and inequalities? Can it speak to a world of death and terror?

When Isaiah speaks the Word of God to the exiles he lets them see what can’t be seen, and makes them believe what they can only know by trust in the one who speaks to them. The Word makes them part of the story again, the story that began at the beginning when God said “light” and there was light, the story that saw their ancestors freed from bondage, the story that seemed to come to an end, but now God says to them, “No, it’s not ending. Not at all. I will lead you through the desert of your journey into my own future.” And what will it be like? It will be like this:

“You shall go out in joy, and be led back in peace; the mountains and the hills before you shall burst into song, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. Instead of the thorn shall come up the cypress; instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle; and it shall be to the Lord for a memorial, for an everlasting sign that shall not be cut off.”

And let the people say: Amen.

I preached this sermon at the New England Pastor’s Meeting of Confessing Christ, West Boylston, Massachusetts, on September 26, 2013.

But the Lord said to me: Do not say ‘I am only a boy; for you shall go to all whom I send you, and you shall speak whatever I command you.’ Jeremiah I.7

It is good to be back with you. I so enjoyed being here on Epiphany Sunday for Pastor Mike’s installation. It was cold then. It is not cold today. I have a small confession to make. Mike e-mailed me “We don’t wear robes in the summer.” And I e-mailed him back, “Can I wear one. I’m kind of a robe guy.” So I brought a robe and a stole up here to Dover, but then I realized I was preaching about opening oneself to new experiences and insights, so I’ve decided not to wear one. You know, to walk the walk as well as to talk the talk. I am also wearing a blue shirt for the first time in forty years, because I’m kind of a white shirt guy, too. So I’m really being daring today.

Will you pray with me:

Gracious God, through the written word, and through the spoken word, may we behold the Living Word, even your Son our Lord, Jesus Christ. Amen

I was just twenty-six years old when I graduated from seminary and became the pastor of the Congregational Churches of West Newfield and Limerick, Maine, just over the border and up the road about an hour from here. That was nearly forty years ago.

I grew a beard to look older and wiser than my years, but I’m pretty sure it didn’t fool anyone. I’ve learned a thing or two about the ways of the world and the church and myself, but when it comes to the ways of God I still stand in awe before the mystery of it all as much as I did back then.

But I will tell you one thing I have learned. You have to be open to hearing the voice of God from unlikely people and in unexpected situations. This is a humbling truth, and there is a kind of Socratic inversion about it. Remember how Socrates said of himself: “I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.”

Likewise, the people who think they always know what God is saying tend to be the ones least open to hearing from God, and are therefore the least knowledgeable.

Because if we decide in advance where and when and through whom God will speak, we severely limit our capacity to hear from God.

There are many reasons we close our minds and hearts to those through whom God speaks.

Perhaps we think someone is too young to speak for God. In our Old Testament reading today, Jeremiah tells God just that, that he is too young to be a prophet. God rebukes him, saying: “Do not say ‘I am only a boy; for you shall go to all whom I send you, and you shall speak whatever I command you.’” Jeremiah I.7

I remember when I was young being frustrated that older people often found it hard to see me as someone with something to say because of my age. Now that I am not so young, I have to resist the impulse to dismiss the insights and wisdom of the young, and to tell the truth, I find myself more and more learning from those who are younger, which is an ever-expanding group.

My twenty-nine year old daughter, Rebecca, was just ordained to the ministry in June. I have heard her preach several times now, and, if I do say so myself, she is pretty good. But sometimes when I am listening to her, my mind is saying, “How can this be? Is this my daughter? I remember the day she was born as if it were yesterday.”

And you have a daughter of this church being ordained soon, Emily Goodnow, a schoolmate of my daughter’s from Yale Divinity School. And perhaps some of you who watched her grow up in this congregation wonder, “How can this be? I remember when she was just a girl in Sunday school.”

Recall when Jesus went to his home synagogue to preach his hearers said, “Isn’t this the carpenter? Isn’t this Mary’s son and the brother of James, Joseph, Judas and Simon? Aren’t his sisters here with us?” And they took offense at him.” (Mark 6:3)

His youth and their familiarity with him kept them from hearing him.

What else keeps us from hearing God speak to us? It wasn’t so very long ago that the conventional wisdom in the church was that preaching the Word of God was a man’s vocation. There are still Christians that believe that.

When I was growing up there were no women ministers in my church or in my experience. When I was at Andover Newton one of my teachers, Emily Hewitt, was one of the first 11 women ordained in the Episcopal Church. It caused quite a stir at the time.

As I was preparing this sermon I wondered what she was doing. So I Googled her, and I discovered that she later went to Harvard Law School, became a lawyer, and is now the Chief Judge of the United States Court of Federal Claims. Why would the church want to deprive itself of the talent of someone like her?

But for a long time we did keep women from using their gifts and talents. It was a widely accepted convention.

For example, and I am really dating myself now, but when I started my ministry in Maine, there were only male deacons, who served communion. The women, called deaconesses, set up the communion and cleaned up after. That was the way it had always been and it was accepted. But we went through a change. We saw the basic unjustness of this arrangement, and we changed it.

And so we changed our ideas about who could preach the Word of God, and now women ministers, and very talented ones like Rebecca and Emily, are a commonplace in our churches.

When John Robinson, the pastor of the Pilgrims in Leyden, addressed them before they shipped off to the New World, he preached a sermon to them. And in that sermon he said, “God hath yet more light and truth to break forth from his Holy Word.”

This openness to new light and truth is very biblical. Our God was always doing the unexpected. Even the people God chose to speak on his behalf or to carry out his plans were seldom what one would expect.

Think about some of them with me: Jacob was a liar, a cheat, and general scoundrel. He tricked his father, stole his brother’s birthright, and had to leave town in the dark of night. Yet he became the Father of a Nation and was given the name Israel.

Moses, God’s spokesman, said, “Not me, Lord, I’m not a good speaker. God said, “I’ll send your brother Aaron with you. He can do the talking.”

The prophet Jeremiah, who we heard about today, said, “I’m just a boy.”

And Mary, the mother of our savior, was a humble unmarried teenage mom.

These instruments of God go against our human expectations, but God uses all sorts and conditions of men and women to speak and act on his behalf.

And so we have had to expand the circle of those who preach, bringing in women within the lifetimes of many of us in this room.

And we are continuing to expand the circle. For example, in the church where I worship our pastor is gay. And he is married. And he and his husband just last week adopted a baby boy.

And that is new to me. And because of that it have been a bit of a challenge for me to get my mind around, because even a decade ago a gay, married pastor with a child was not part of my experience, or the experience of many for that matter.

Last year, during our interim period, I was praying for God to send us a faithful pastor and preacher. And God did, because this pastor is a rock-solid Christian, born and raised in the church, and I never hear a sermon of his without hearing something of the voice of God in it.

The world around us changes. The contexts in which we preach and hear changes. I am reminded of the story about Will Campbell, the white civil rights leader who marched with Martin Luther King. He was a Southern Baptist, and he was asked if he believed in infant baptism. “Believe in it? I’ve even seen one!”

So once again we have had to expand our thinking about who we think we might hear God’s Word from. We have had to expand the circle.

Because God calls a variety of men and women to speak on his behalf, and they come in a variety of shapes and sizes, races, tongues, and sexual orientations. And the truth is we need to hear from them all.

Because the Word of God doesn’t just drop from the sky. The Christian faith is a mediated faith, coming to us through the words of others. We have the words of the Bible, and the Word of God can be discerned in them, but they themselves are not the Word of God. No, to hear the Word of God we need human interpreters, which is one of the tasks of the church.

One way of thinking about this that has helped me was put forth by the great Swiss theologian, Karl Barth. He wrote about the threefold understanding of the Word of God. First, there are the written words of the Bible, then there are the spoken words of the preacher, and finally, and most importantly, there is the living Word, Jesus Christ.

This living Word is mediated through both the written words and the spoken words. The prayer I began my sermon with is based on this idea: “Through the written word, and the spoken word, may we behold the living Word, even Jesus Christ our Lord.”

So we need people in the church to mediate the Word of God to us, to make it real for us. And this happens in community and in relationships with real people living real lives, with real talents and struggles. We need all kinds of people, so that you can even hear a sermon from someone like me with a brain injury.

Those of you who were here for Mike Bennett’s installation in January will remember that I preached a sermon called “Ministry is not a Commodity and Ministers are not Appliances.” And in that sermon I said this: “Mike embodies what the great preacher Gardner Taylor was after when he advised preachers “to look beyond the peripheral signs of preaching greatness to the real source of pastoral insight–the common bond with one’s hearers provided by suffering.” And I would expand Taylor’s words to include not only suffering, but all manner of shared life-experience, the kind that happens in community, the kind that happens day to day in the church.

And I said this to you: “If you let him, Mike will share your lives, will rejoice when you rejoice and weep when you weep, and will become your pastor.”

And by all indications it seems that, nearly a year into your relationship together, you are finding that to be true.

But the very best preacher in the world does not make the Word of God alive by himself or herself. For that you also need good hearers, ones open to hearing things that they may not have heard before, that may challenge them, prod them, even make them unhappy or angry.

But by being open to the unexpected, hearers may well hear things that please and delight them, things that make them wiser and stronger and more faithful. And may open them to larger truths, to new wonders, and, above all, to the amazing grace and the vast love of God for us in Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

I preached this sermon on August 25, 2013 at the First Parish Church, Congregational (UCC) in Dover, New Hampshire.

Has this ever happened to you when you are captive in a pew?

I was at a house of worship not long ago, where the preacher is a long-time friend of mine. I was looking forward to hearing him preach, and I when he started I was pleased with his voice and his manner. He said some wise things and I could feel that he was wrapping up, but then . . . he started on a new tack. He did this three times, and each time I thought he was done. It was a very long sermon; in fact it was three long sermons.

The next day I was at a seminar with a bunch of pastors and I mentioned the experience to my friend Scott, who provided me with one of my favorite axioms: “If you don’t know what you are doing, you don’t know when you have done it.”

Arnold Kenseth wrote some wonderful poetry, but he never lost touch with the challenges of having to stand up on your hind legs each Sunday morning and try to make words become the Word for the people. Here he names the impossibility of such a task, a task he and all preachers must nonetheless take up each week, because that is what God has called us to do. This is one of my favorites of his:

SUNDAY’S HOUR